October is domestic violence awareness month, a time police and advocates have set aside to highlight how common intimate partner violence is and encourage people to seek help. It’s acutely problematic in Fresno County, where authorities receive a shockingly high number of calls reporting domestic violence. That left our news team wondering: Why?

Domestic violence is a huge problem across California, especially in the Central Valley. In 2014, Fresno County alone received more than 6,000 calls to 911 reporting domestic abuse. That’s why the Fresno County District Attorney’s office has made prosecuting it one of its top priorities.

Assistant DA Steve Wright, who oversees his office’s domestic violence unit, says the offense has broad ripple effects that can have far reaching consequences. “The abuse is affecting not only themselves but their family and their friends,” Wright says. “It’s devastating on young children to see this type of abuse in the household.”

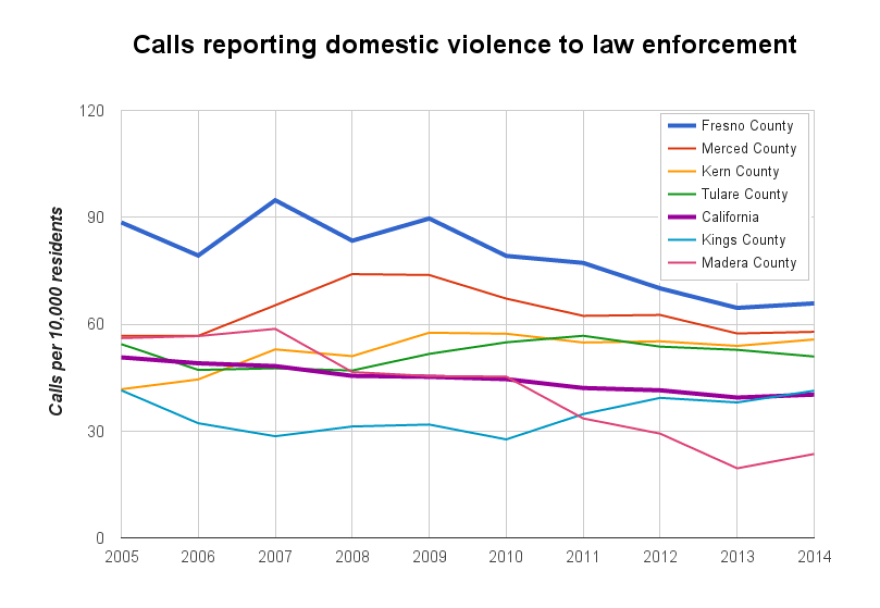

Fresno County's rate of calls reporting domestic violence is 63 percent higher than the state average.

The DA has also partnered with the police to find abusers and with local nonprofits to help victims.

So why are we talking about Fresno County specifically? It’s because it looks like this kind of abuse is a bigger problem here than in the rest of the state. Per capita in Fresno County, that call rate reporting domestic violence is 63 percent higher than the state average.

This jumped out at us. Why are the numbers so high? Is Fresno County really that much more violent than the rest of the state? Wright doesn’t know the answer to either question. But he says understanding the root problem is a priority; it could mean they are better able to help victims.

“The ‘why’ matters in that if we know why our rates are so high, we can try and do something to prevent those additional victims from being victimized,” he says. “If we know what’s causing that high rate, we can do something about it and prevent those future victims.”

The assistant DA may not know the reason, but we assumed someone would. So we set out for answers.

We began with one of Fresno County’s most respected organizations that address domestic violence: The Marjaree Mason Center. It’s a non-profit that offers emergency shelters, counseling and other services for victims of domestic abuse. Executive director Nicole Linder offers up one theory for why the numbers are so high in Fresno County. “It doesn’t explain the behavior, nor does it condone it, but things like substance abuse and poverty, which obviously are huge issues to Fresno County, highly escalate levels of domestic violence,” Linder says.

Steve Wright seconded that opinion. But here is the problem with pinning high rates of domestic violence on poverty, unemployment and substance abuse: Those factors are not appreciably higher in Fresno County than in neighboring counties. But our rate of calls reporting abuse to police is. The call rate per capita is 18 percent higher than in Kern County, 60 percent higher than in Kings County, and almost three times the rate in Madera County.

We knew there had to be more.

We learned another theory when we ventured out of the city of Fresno. We visited a community service center in Huron, a small town on the southwestern edge of Fresno County. It’s run by Jeannemarie Caris-McManus. She agrees that economics play a role in the county’s high call rate, but she thinks geography is a major factor, too. Fresno County is huge, so help may be far away. A victim in a tough spot might have a difficult time escaping, leading to repeat 911 calls.

“We're 65 miles from Fresno, and people here don't have transportation. So if somebody is in a domestic violence situation, they don't want to go to the Marjaree Mason Center,” Caris-McManus says. “There's nothing wrong with the Marjaree Mason Center, and we will refer people there, but almost nobody ever goes.”

This underscores a real problem, but it’s not what’s driving the county’s numbers up. Call rates from the cities of Fresno and Clovis are still significantly higher than the county average, so there’s no way rural calls are swinging the data.

There is one more perspective we encountered: There isn’t significantly more domestic violence in Fresno County than in neighboring counties, it just gets reported more—in part because prosecutors and police have focused extra resources on it. We heard that theory from Fresno County Sheriff’s Sergeant Jeff Kertson.

He says if domestic violence victims, their neighbors, friends and family members, think they can get help from calling the police, perhaps they’ll be more likely to call. “Maybe we just have a higher level of reporting based upon the high level of training that we give,” Kertson says--“our advocacy program and the partners we have with the Marjaree Mason center, and the strong working connection of law enforcement and our victim advocates.”

"They might know that there's a place that you can call if this is happening to you and they can help you - and sometimes that's all that someone needs in order to make that call."

That’s hard to prove, but he wasn’t the only one to put forward that hypothesis. Jacquie Marroquin of the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence agrees that strong, visible support systems are important in showing victims that help is available.

“They really develop some roots in the community; the community knows about them,” she says. “They might not know all the things they do, but they might know that there’s a place that you can call if this is happening to you and they can help you—and sometimes that’s all that someone needs in order to make that call.”

She also throws in a word of caution: we should be careful assuming poverty is one of the fundamental drivers of domestic abuse. Domestic violence occurs in all socioeconomic groups,” she says, “and I think the difference here is access to support.”

She says the reason domestic violence may seem correlated with poverty is that that’s what shows up more on the radar. Wealthier victims are more likely have the means to get themselves out of abusive situations. It’s poorer people who are more likely to seek services and end up in the statistics. Plus, abuse can take many forms in addition to physical violence.

And for the multitude of guesses we ran across, the reality is that domestic violence is probably even more common than these data show. The Department of Justice estimates that only about a third of incidents actually get reported—meaning the real rate of domestic violence in the Central Valley might be even higher.