Here in North America, Switzerland may be known for snowy mountain tops, raclette cheese, and yodeling. But the landlocked, Central European country is also home to one of the biggest and most ambitious science endeavors ever undertaken. And though it’s nearly 6,000 miles away, the San Joaquin Valley is leaving its mark there. We spoke to some Valley locals at the European Organization for Nuclear Research, or CERN.

Enter CERN as a tourist and one of the first sights you’ll see is the so-called synchrocyclotron, a small particle accelerator that once was CERN’s flagship experiment. Built in the late 1950s, this Cold-War-Era machine is now retired, but it set CERN on a trajectory to become the world leader in nuclear and particle physics.

Indeed, half a century later, CERN built a particle accelerator 300 feet below the synchrocyclotron that’s a hundred thousand times more powerful. The Large Hadron Collider, switched on in 2008, is a circular tunnel 17 miles around that smashes protons together at velocities approaching the speed of light for detectors to observe the particles that ricochet out. In 2013, the collider earned CERN a Nobel Prize for finally observing the Higgs boson, nicknamed the “God Particle.” Physicists had been searching for the Higgs for decades.

At first glance, CERN appears full of juxtapositions like these two particle accelerators. Sleek modern architecture rises up out of brutalist, concrete office buildings. Towering sculptures of wood and steel commemorate the study of particles that are less than a billionth the size of a grain of sand. And the sprawling campus straddles two countries: Switzerland and France.

But CERN’s multiple personalities are part of what makes it work. CERN is operated by close to 18,000 staff, students and visiting scientists from more than 100 countries.

And so Fresno State students Jennifer Tyler, a year into her Master’s degree, and Valentina Lee, who earlier this summer earned her Bachelor’s degree, fit right in.

Tyler and Lee are summer students at CERN. They’re spending a few months here between semesters, working alongside staff scientists using the Large Hadron Collider to address unanswered questions about the particles that make up the atoms that make up nearly everything we see. “We use the collector to collect protons to find out more fundamental particles,” Lee says, “and where our universe comes from and how it started.”

Fresno State began collaborating with CERN in 2008, thanks to a physics professor named Yongsheng Gao who established Fresno as the first California State University campus there. Though he’s since brought other schools onboard, Fresno was the only CSU campus to have taken part in the Higgs research that earned the 2013 Nobel.

That history called to Lee, who came to Fresno State from Taiwan. “When I started applying to Fresno State, I looked at this program and I was like, ‘oh, this program is awesome,’” she says. So that’s one of the reasons I applied to Fresno State.”

This is her second summer at CERN. It’s Jennifer Tyler’s first, though she hopes to finish her Master’s degree and ultimately her Ph.D. there.

Since 2008, 47 Fresno State students have summered at CERN, as well as 35 from other CSU campuses. Roughly 100 U.S. universities and labs collaborate with CERN.

Tyler says she’s proud to represent Fresno State abroad. “You've got MIT, you've got Stanford and Harvard and all these other really incredible universities, then there’s Fresno State, which is an amazing university but it’s not a top tier research institution,” she says. “So we have the opportunity to show our stuff.”

But both students agree: This work is about much more than Fresno State. It’s about the ambitious and daunting process of bringing thousands of scientists together to work toward one shared and somewhat nebulous purpose: Study minuscule particles to understand the universe. “On paper, this sounds like the worst idea ever,” Tyler says. “But the fact that it worked, and it still works and will continue to work is just a triumph of science collaboration.”

Many physicists worried that after the discovery of the Higgs boson, CERN would lose its purpose. But Tyler and Lee say: No way. There’s still the search for other theorized particles like gravitons and the quest to understand dark energy and dark matter. “It might not be as glamorous or catch worldwide attention as the Higgs boson does, but it'll continue to fill out our knowledge of the universe and how it works,” she says. “Life at CERN still has meaning and it will have meaning for a very, very long time.”

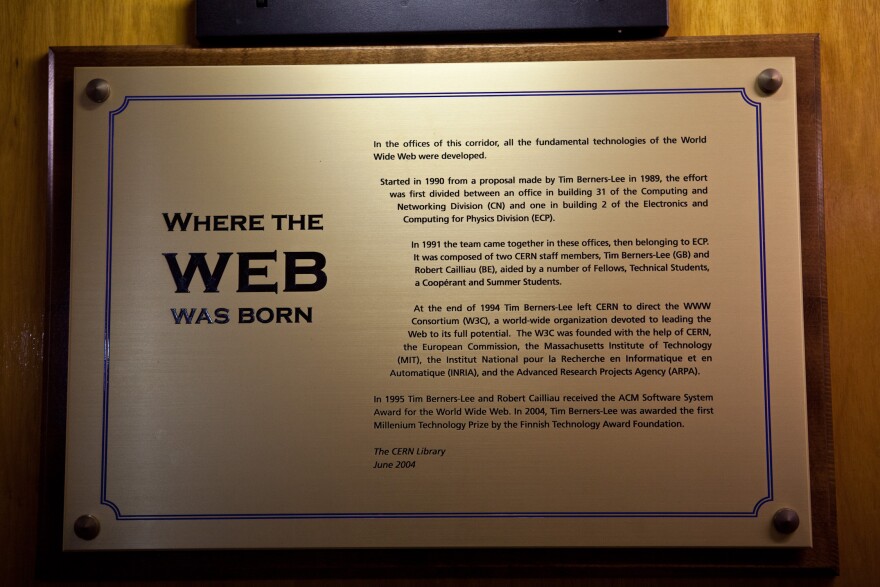

And who knows: Maybe some small discovery now will end up as important as another CERN invention from decades ago – the World Wide Web.