After it was first reported in March, the recent E. coli outbreak in romaine lettuce appears to be drawing to a close. But that’s only after it sickened 172 people in 32 states and resulted in one death in California. Why did it take so long to get under control? One reason is that produce can be difficult to trace from farm to fork, through the sometimes dozens of suppliers, distributors and wholesalers that make up the produce supply chain—but two recent initiatives are attempting to change that.

Gerawan Farming is one of the nation’s largest suppliers of stone fruit. Its sprawling Sanger warehouse full of clunking sorting machines and clickity clacking conveyor belts produces millions of pounds each year of peaches, nectarines and plums.

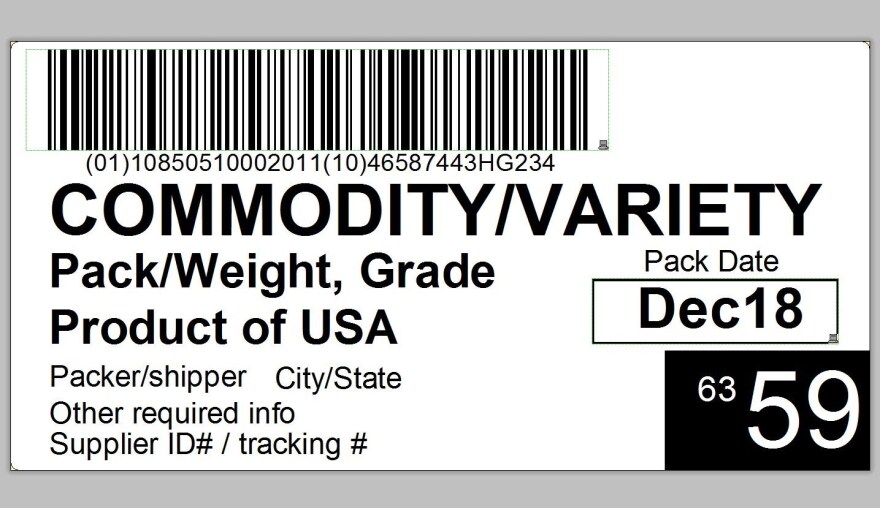

Vice President of Technical Operations George Nikolich claims the company can trace every nectarine packaged today from field to bin. And so can Gerawan’s customers, thanks to a special label slapped onto bins by a pneumatic arm. It’s “about a 2 by 4 inch label or thereabouts,” Nikolich says, “and it has a barcode with a very long number underneath it”—much like an oversized version of a retail sticker.

By scanning this label, Nikolich’s customers can trace these nectarines back not just to Gerawan, but to the packing lines and even the fields they came from. “It's an important piece of communication between us and our customers,” he says.

But traceability like this is not the produce industry standard. Nikolich explains each company typically maintains its own recordkeeping standards. Some may even still use paper. Because Gerawan’s fruit is grown and packaged in house, tracing its nectarines is relatively simple—but that information can get lost within bigger companies, or further down the supply chain. “You’ve got hundreds of thousands, millions of individual products, and you’re often tracing them from the orchard to the consumer,” he says. “There’s no standardized system to accomplish that.”

This 2-by-4-inch label is a first step toward a standardized system. It’s the keystone of the Produce Traceability Initiative, or PTI. It’s a voluntary program, but it’s estimated that more than half the companies in the U.S. produce supply chain take part.

It’s tough to determine if it’s yet making our food safer. But it does serve as the backbone for a newer, higher-tech initiative. And the advantages are clear for suppliers like Gerawan and their customers. “We’ve got our dialect, they have theirs, and you need a translator,” Nikolich says. “PTI compliant labels are trying to serve as a translator between producers and their customers.”

The Produce Traceability Initiative was born around 10 years ago after a 2006 outbreak of E. coli in spinach killed three people and sickened almost 200. “The industry got together and said what we have in place is not good enough, we need to be better,” says Ed Treacy, a supply chain expert with the Produce Marketing Association and one of the industry leaders of the PTI.

He says in the case of an outbreak, tracebacks are typically done in baby steps: Finding the grocery store where the problem food was sold, looking up purchase orders and then fanning out to contact the many suppliers that could have shipped it. The search can take months, and many outbreaks blow over before investigators can determine the root cause.

Treacy says so much could change in outbreak investigations if each case of produce had a unique identifier it took with them through the supply chain, like a standard barcode known as a GTIN. “[The search] gets much more narrow if they can go back through their records and can identify: On this date, we shipped five cases of spinach and here was the lot number and GTIN that was on that case,” he says.

Stephen Ostroff, Deputy Commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine with the FDA, agrees there’s room for improvement in our food supply. In this most recent E. coli outbreak, it’s not yet clear how many companies were using PTI labels. But Ostroff believes if they all had, the investigation would have markedly improved. “I’d like to think that it would’ve made the tracebacks that we were engaged in not only considerably easier but also considerably faster,” he says.

As industry adoption of the PTI has grown, it’s difficult to tell if investigations really have gotten any faster. Speed is not tracked as easily as illnesses and deaths are. But data from the CDC do show that over time, more and more outbreaks are getting traced back to their source, rather than remaining a mystery.

Still, tracing food could get even faster and better. IBM is building upon the Produce Traceability Initiative to create a food safety system based on blockchain, the technology used to publicly track Bitcoin transactions. Using blockchain, every step in supply chain would be recorded and stored in one centralized location in the cloud. Brigid McDermott, Vice President of the IBM Food Trust, says: Just imagine what that could mean for food tracebacks. “If you could go from it taking a week or weeks to identify the source of the problem to taking seconds, this has a real impact on people’s lives,” she says.

So what’s keeping these from becoming widely adopted? For now, IBM’s Blockchain initiative is limited to a few major distributors. The Produce Traceability Initiative is available to anyone, but it’s costly. Serhat Asci, a professor of Agricultural Business at Fresno State University, says companies are more likely to adopt systems like the PTI if they have pressure from consumers. “It all comes from customer concerns,” he says.

Still, regardless of how we trace food back, there’s still one factor that will always limit how quickly investigations can happen: Our ability to remember what we ate. It’s tricky, especially when it comes to processed foods. But it’s a lot easier with fresh nectarines.