Author Tim Z. Hernandez was digging through old newspapers at the Fresno County library when a dramatic headline from the late 1940s captured his attention.

“I stumbled upon this headline that said, ‘100 people see a ship plunge to the earth’ or something like that. It was just really a captivating headline. I instantly realized after reading it that it had to be tied into Woody Guthrie’s song,” says Hernandez.

The sky plane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon/A fireball of lightning, and shook all our hills/Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?/ The radio says, “They are just deportees.”

That song is called ‘Deportee.’ The folk musician wrote the lyrics after hearing of a harrowing plane crash that occurred in Fresno County in 1948.

The plane, chartered by the U.S. Immigration Service, was transporting 28 Mexican nationals from Oakland to El Centro, near the U.S.-Mexican border.

The plane's wing caught fire and broke off, scattering body parts through Los Gatos Canyon near Coalinga.

W.L. Childers, who lived on a ranch in the canyon, witnessed the crash and its aftermath. His quote ran in the Fresno Bee in 1948.

“The plane was headed east about a mile high. I was watching it when I noticed a streak of smoke trailing off the left motor. The left wing then separated from the body of the plane and the fuselage and the right wing began to spiral down toward the earth. As I watched, I could see bodies separating from the wreckage as they either jumped or were thrown clear,” said Childers.

All 32 onboard, including the flight crew and an immigration officer, died.

The crash made national news. But the names of the victims did not. Locally, the Fresno Bee published some names. But an Associated Press article that ran in the New York Times the day after the crash only named the crew. It simply referred to the passengers as “28 Mexican deportees.”

That angered Guthrie, and inspired his song. In it, he assigned symbolic names to the victims. It’s performed here by his son, Arlo Guthrie.

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita/Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria; You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane/All they will call you will be “deportees.”

As Hernandez reflected on the news accounts of the tragedy and the song lyrics, he instantly knew he had another book idea.

“Being in that sort of mindset, and looking at these 28 lives that had perished in this plane crash in 1948, and didn’t have the dignity of their names afforded to them in the media at the time, was something that I think just felt compelled to want to find their story or put their story back,” says Hernandez.

“That's really was captured my attention. How can I not only find their names, maybe, but also give them their story back, to some degree?”

For Hernandez, piecing the story back together – 65 years later – has become a multi-year journey. His goal is to reconstruct the accident, and the lives of the people impacted by it.

“For me, that’s what the book is about. It’s about capturing the ripple effect of all the lives that this one tragedy touched, back then and even today,” says Hernandez.

That journey took him to the site of the crash. It’s located in a quiet, lush canyon.

“It’s nice here. It’s like someone’s backyard, it’s very pretty, it’s a cattle field right now, we had to step over the cow pies on the way out here. It’s very nice, pine trees, canyon, creek right here, but it’s a very famous crash site right here, also.” says Coalinga resident Larry Haws.

His mother was just a child when she saw the wing of the plane fall off, and land just steps from her grandmother’s home. He, of course, didn’t witness the crash, but he was willing to show me where it happened. We climbed under some barbed wire and walked through a field to reach the site, which today is unmarked.

“The plane came in, and barely made it over this little ridge we see right here to our right, and it was spiraling, and it barely made it over that, and it crashed head on into this creek bank, right here, and it caught these three trees on fire.”

Hernandez also connected with Haws’ aunt, June Leigh Austin, who was almost 10 years old when the plane crashed near her home in the canyon.

“I didn’t see the plane go down, although several members of my family did. I arrived there on the school bus, after it was down and they were still pulling the bodies out, and all the things were happening,” says Austin.

She recalls that parts of the passenger’s bodies were strewn across the canyon.

%22There%20were%20bodies%20scattered%20all%20over%2C%20so%20it%20took%20a%20lot%20to%20even%20find%20everybody%2C%20all%20the%20pieces%20I%20should%20say.%20I%20don%27t%20know%20that%20there%20were%20any%20bodies%20totally%20intact%2C%20and%20none%20were%20identified.%20There%20were%20mainly%20just%20bits%20and%20pieces.%22%20-%20June%20Leigh%20Austin

“There were bodies scattered all over, so it took a lot to even find everybody, all the pieces I should say. I don’t know that there were any bodies totally intact, and none were identified. There were mainly just bits and pieces,” says Austin.

Austin, who is 74, remembers the incident like it was yesterday.

“It was a horrendous thing and I don’t know if it was worse on me as a child or not, but it certainly stayed with me all my life. The sight and the smell, and everything that happened, it affected all of our family,” says Austin.

We died in your hills, we died in your deserts/We died in your valleys and died in your plains. / We died ‘neath your trees and we died in your bushes/Both sides of the river, we died just the same.

But Hernandez says a major component of this story is still missing.

Hernandez combed through records to properly identify, as best he could, the 28 Mexicans who died in the crash. He recites the names in this version of ‘Deportee,’ which he recorded with Fresno musician Lance Canales.

He has learned a little about them: He’s determined that some were braceros, or guest agricultural workers. One person, he says, had a laundry workers union card in his back pocket. Another worked in a foundry in Sacramento.

“What I don’t have, though, still, at the end of the day, are the voices of the 28 people who died on board,” says Hernandez.

“Virtually nothing, about how to locate the surviving families of these plane crash victims – 28 deportees, or Mexican nationals. That’s why I feel like, right now, I’m not satisfied with moving forward with this book at this point, until I feel like I’ve exhausted every resource to find that family,” says Hernandez.

That’s where this historical event becomes a modern-day, community endeavor.

Rebecca Plevin: “If you were reaching out to those families, what would the message be?” Tim Hernandez : “Uh, call me!” (Laughs.)

Hernandez acknowledges that any survivors of the crash victims could be several generations removed. But if a grandchild, or great-grandchild, or a survivor has even a photo of one of the victims, that would make a difference.

“Sometimes, just seeing a photograph can speak volumes, as we all know. Even that would be something, putting a face to their names. It’s going beyond a step beyond just their names,” says Hernandez.

There’s another way that Hernandez is breathing new life into this story and its characters.

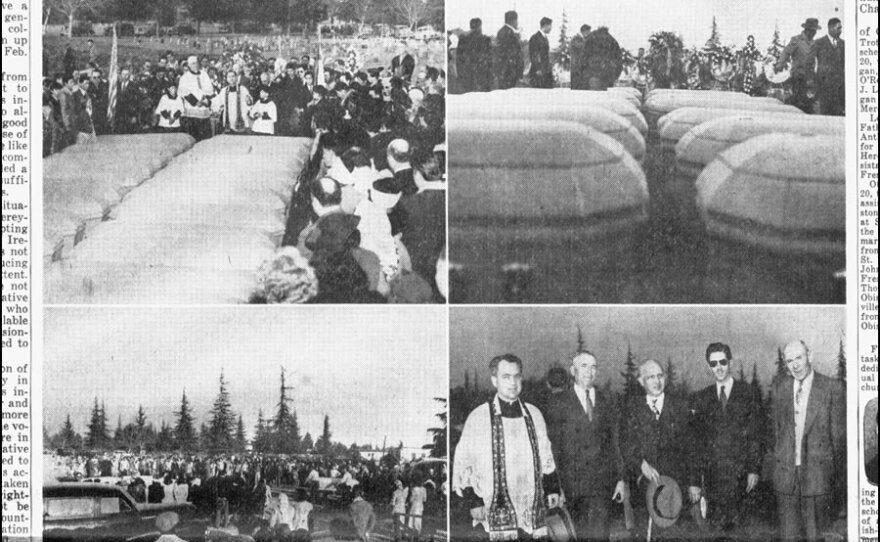

He learned that the 28 Mexican citizens were buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno. Their graves are marked with one headstone.

“It’s a 12 by 24 bronze memorial, as you can see, it’s weathered, it’s patina-ed. It says, ’28 Mexican citizens who died in an airplane accident near Coalinga, California, on January 28, 1948,” says Carlos Rascon.

He is the director of cemeteries for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Fresno. He, like Guthrie and then Hernandez, was moved to learn that the 28 people were buried, without their names inscribed on a headstone.

“There are people that are buried here that are John Does, Jane Does. And if you had a family member that went missing, and later on you find out that they’re actually at a cemetery and they have no names, that would strike me as – why, why isn’t their names there? It’s unsettling to me, it’s almost like it’s unfinished,” says Rascon.

Rascon and Hernandez came up with a plan. They are raising $10,000 to establish a memorial to the victims of the plane crash. The memorial will include the names of each of the 28 Mexican citizens.

“My idea, as part of the inscription, is to have one leaf represent each of the 32 people. 28 of them are here, but the other four were buried elsewhere. And if you hear Woody Guthrie’s poem, it says, ‘they were scattered like dry leaves on our topsoil,” says Rascon.

Is this the best way we can grow our big orchards?/Is this the best way we can grow our good fruit? To fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil/And be called by no name except “deportees?”

Hernandez encourages people to embrace this part of our history.

“We want the community to feel that this is part of their history as well, not just California history, but American history, as Woody Guthrie told us. At the end of the day, our names are really what we have,” says Hernandez.