For years California winemakers have earned their reputation by producing big, bold wines, often known as "fruit bombs." They've also effectively used science and technological advances to make the state a global behemoth in the worldwide industry.

But there’s also something else going on in California - a new generation of winemakers who are looking to old world traditions for their inspiration, and in the process are creating something truly unique.

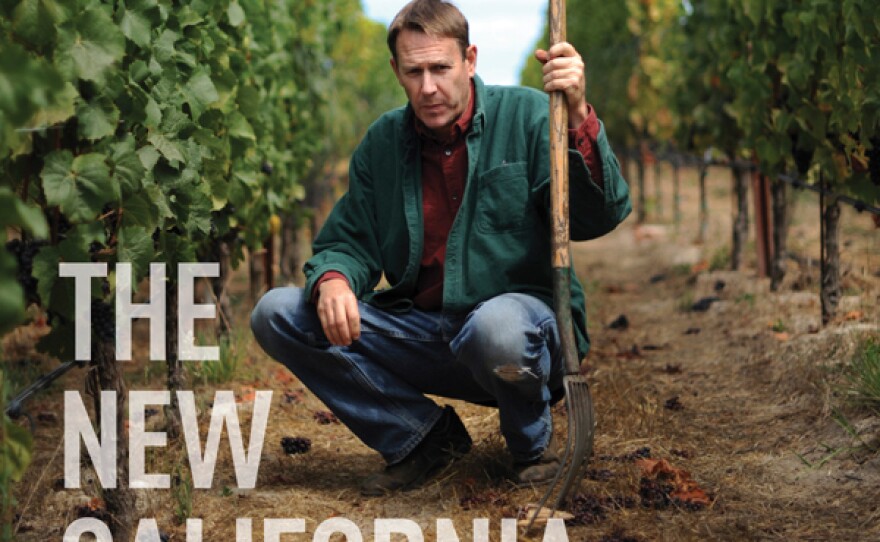

They’re the subject of a new book " “The New California Wine: A Guide to the Producers and Wines Behind a Revolution In Taste” " by Jon Bonné, the wine critic for the San Francisco Chronicle.

In it, Bonné travels the state to bring us the stories of the people behind this rebellion against what he calls "technocratic" style of winemaking. Instead, these small winemakers are turning to old world traditions for their inspiration, and in Bonne's view, fulfilling the promise of California's many unique terroirs.

Bonné also traveled to the San Joaquin Valley to report on the industrial side of the wine industry. From Madera County he tells the story of the essential role that valley wine growers play in the state's wine industry, and how valley viticulture and enology programs at schools like Fresno State and UC Davis play a big role as well.

Interview highlights:

On the “revolution” in California’s wine industry:

It [revolution] was not a word we chose lightly. And it’s a word I’m sure some folks think is probably too strong. What I would describe it as, is wines that do what California has historically done best, which is to offer both the complexity and the nuance that people have often associated with the old world, with the exuberance that they can find in California.

For a long time most of California wine was trying to emulate the first. And then for about 15 years or so, it was really chasing the second, in what I call the era of “big flavor.” And I think what we’re seeing now is people turning away from just sheer impact to wines that offer a true perspective on the glorious diversity that California can offer.

On “technocratic” wine making versus “artistic” wine making:

I think technocratic is simply acknowledging the way that the post-war industry in California was built up, in no small part with the work from UC Davis, but also Fresno State and other places, placed an enormous focus on the science of winemaking. And that’s not a bad thing. You want to be able to employ it in appropriate ways. But especially as the industry grew really faster than anyone could keep up with it, it became very convenient for science to be the only mode of work in the cellar, and for people to simply run the wineries on the numbers.

And I think anyone who really believes in the timelessness of wine and the culture, has to accept that you just don’t make great wine that way. You have to pull away and really see what the specifics of the place that you want farm can give you, what the vintage will give you, rather than simply adding a commercial yeast that will give you one flavor or another, making sure you hit all your chemistry, and following quite literally a textbook approach of winemaking.

"It was very important to me when I was reporting for the book, that I get out and I see the side of California that I hadn't really seen, and I think almost no wine writer ever goes to see." - On the San Joaquin Valley's wine industry

About going to “the abyss” where few wine writers ever go, the San Joaquin Valley:

It was very important to me when I was reporting for the book, that I get out and I see the side of California that I hadn’t really seen, and I think almost no wine writer ever goes to see. So I reached out to some folks and they wanted to go to maybe Clarksburg in Lodi, and that was fine. But I said I want to get to the thick of it. I want to see the real heart of what cheap table wine comes from, and so ultimately we made our way to Madera, and to me actually it was one of the most interesting parts of the book…But it was really crucial to me to get out and see what industrial scale farming looks like. What it’s like to farm French Colombard at say 25 tons an acre.

The most significant thing to me was that it is possible to make that a profitable venture, when you look at it simply as large scale farming would be for any other crop. But my takeaway being, the economics of farming for really cheap wine are brutal, and I think have probably over time, not served growers terribly well. I think growers if anything are now more worried and more distrustful of large wine companies who have an extraordinary way of fiddling with contracts to suit their needs. I wanted to go to the absolute opposite end of where $20,000 a ton Napa Cabernet farming is, just to see how the world works. And it was eye opening... It was neither as dramatically unsettling as I thought it might be, nor really inspiring. It was good to see that there is a way to make those numbers work, but at the same time, I had to keep asking myself, “what’s the quality of the wine that those go into?” And is there ultimately a sustainability in growing say a Zinfandel for White Zinfandel at 18 tons an acre, when you have to drill a new well every year at $250,000.

About the “third rail” of California wine – the commonly used additive known as Mega Purple:

Essentially it’s a grape concentrate. They take typically Rubired grapes, which are a cross that was designed in the 1950’s I believe, and really intended mostly for color, and concentrate it enormously. And what it does to wine, and you add it in infinitesimal doses when you’re blending, is two things. It adds color. So from an era when people worried about red wine being deep and inky, it would give that to a wine that was a little bit wimpy. And people rarely discuss this part, it adds just a tiny bit of sweetness. There’s a lot of interest by larger scale wineries in finding ways to add just a bit of sweetness to wine, without necessarily making a full-on sweet wine.

"It's not a fundamentally bad thing if you use it in cheap wine. But it is something where you have to ask if you're paying $80 or $100 a bottle, why couldn't they have done farming right?" - On the use by winemakers of the concentrate known as Mega Purple to give their wines color

So Mega Purple is this very convenient way to tweak not only inexpensive wine, but also and I think this is where it was unsettling to people, often very expensive wines, to add those two aspects, and ultimately try to boost your prospects with critics.

It’s not a fundamentally bad thing if you use it in cheap wine. But it is something where you have to ask if you’re paying $80 or$100 a bottle; why couldn’t they have done farming right so that they weren’t having to add an additive basically at the end, in order to come up with a finished product that was maybe more aesthetically pleasing? Why essentially weren’t they doing their jobs in the first place?

About the often secretive role brokers play in bringing Central Valley fruit to winemakers throughout the state:

That’s always been the promise and the dark edge of the California appellation. If you’re making a California appellated wine, then you might get some of your grapes from Monterey or Paso Robles. But you’re reaching out to a broker and you’re looking for sort of bottom dollar grapes, often from the San Joaquin, and using that to essentially make your numbers a little better. It’s one thing even to do it for a wine that’s just marked California. But when you suddenly see a wine that says Central Coast or even Napa or Sonoma, where’s there’s clearly a little bit of Central Valley fruit used as an extender. I mean, that makes some economic sense, how the industry has operated, and in some ways that historically is how fruit from the Central Valley was harnessed even I would say before the modern era, in the years just after prohibition.

But the flip side is that it really doesn’t give people a sense of what California can do. It doesn’t say “this is the value of Lodi fruit” and Lodi has fascinating, really kind of amazing places to grow wine, especially as you get out into eastern Lodi and you climb into the mountains. And I suspect that if there were more attention that people would start to find additional places. I’m just thinking of somewhere like Oakhurst, where there’s definitely at least a handful of interesting vineyards, as you start to gain a little more elevation, and get back up to places where you get a little bit of cool nights and you can grow really good quality grapes. But that’s just not the way the industry is setup. The industry is configured in some ways to make the consumer in let’s say Kansas or Tennessee or in New York, just think about “California” overall. And I would argue I don’t think that’s ultimately done the growers of California a service. Because it hasn’t let people really start thinking what it means if a wine is from Lodi.

How the viticulture and enology programs at UC Davis, Fresno State and Cal Poly are adapting to this revolution:

I think there’s been a lot of progress. The last time I was at Davis, I was talking to students who were absorbing the science and who were following the standard course at a V&E (viticulture and enology) program, but who also were planning to go off and work with these avant garde producers in France or Northern Italy, let’s say Friuli, and really were using their education essentially for great good. For the opportunity to work in an artisanal mold. To make wines that are very traditional wines, simply with the perspective of good winemaking education. So I think that there’s been a lot of progress, there’s going to keep being progress in terms of wine education. But it’s also always worth remembering that to some extent these programs are largely funded by big wine companies, and so ultimately their great goals are going to be to turn out people who can work for big wine companies.

The New California Wine by Jon Bonné - Excerpt